"A Critical Turning Point": Experimental Humanities Exhibit Explores Names and Their Power to Shape the World

Krista Caballero (right), co-lead of the Experimental Humanities Collaborative Network (EHCN) and co-curator of "To Be–Named," and Vivien Sansour, Distinguished Artistic Fellow at EHCN, pose in front of Caballero and Frank Ekeberg's "Birding the Future" at the exhibit's recent opening in Albany. Photo by Terry Roethlein.

“When colonizers erased a name, they attempted to erase a people and a meaning,” says Krista Caballero, one of the project leads of the OSUN-supported Experimental Humanities Collaborative Network (EHCN), and one of the co-curators of To Be—Named, an EHCN art exhibit on view at Opalka Gallery in Albany, New York that is part of a larger project by the same name.

At the exhibit’s recent opening event, Caballero explains that culturally privileged names can forcibly shape the world. “It’s time to redefine that and think about the words we use,” she adds, summing up what might be described as the core mission of the exhibit and the To Be–Named project.

The exhibit’s website says the show “reflects upon how names are created and used to shape, reshape, and sometimes mis-shape, our worlds, and identities. Artists included in the exhibition investigate, contend with, and complicate naming practices to reveal ways that personal experiences are either shared or collide with collective ones, creating our political, cultural, and ecological realities.” Even the long dash in the title “To Be—Named” expresses the gap between self conceptions prior to naming and after they have been shaped by language and names, according to project leads.

To Be–Named was born out of a partnership between EHCN, Recovering Voices at the National Museum for Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution, and the EU-funded CoLing project. The Hudson Valley show is the second installation of an international touring exhibit that has already been to Germany and will later make stops in Greece, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Palestine, and Republic of Sakha (online).

Seven works shown at all locations concern the loss of identity when names are translated into another cultural context. In addition to Caballero, co-curators of the traveling work include Christian Ayne Crouch (Bard College Annandale, US), Gwyneira Isaac (Recovering Voices), Marta Ostajewska (University of Warsaw, Poland) and Bently Spang (Tsitsistas/Suhtai Nation, Montana, US).

The core group of films, sound installations, and photographs created by international artists is supplemented by works from local artists at each site. Local curators at each site include: Dorothea Schöne (Germany), Krista Caballero (US), Fotini Gouseti (Greece), Sasha Filatova (Kyrgyzstan), Kyunney Takasaeva (featuring artists online from the Republic of Sakha), and Greta de León (Mexico). The Hudson Valley exhibit traces colonial history and injustices, unpacking how they have played out over decades through naming, appropriation, or biased historiography.

Naming, Enslavement, and Emancipation

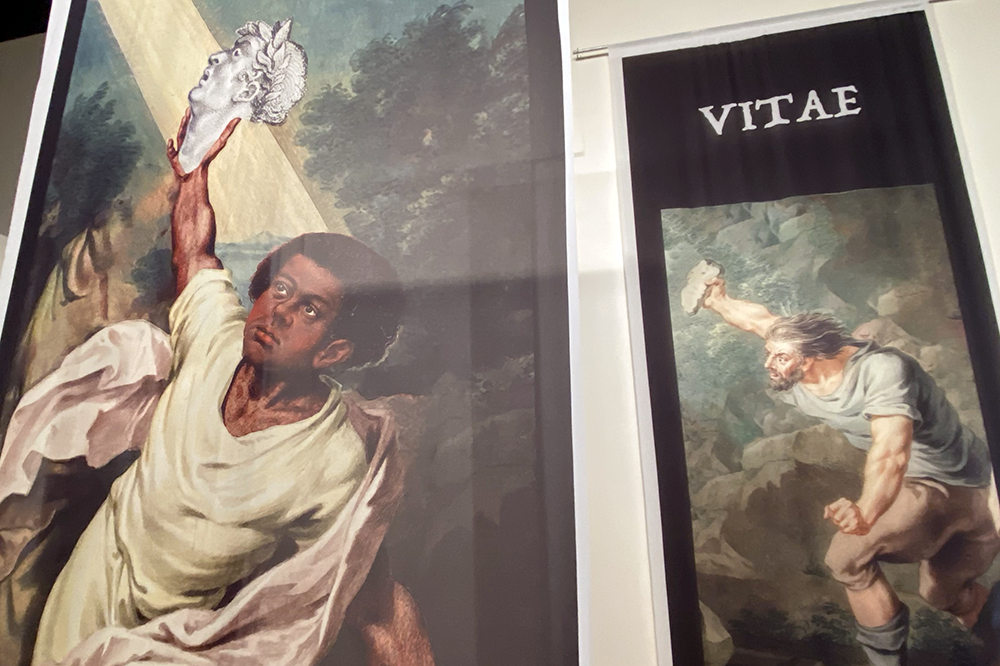

Jean-Marc Superville Sovak’s three digitally printed panels, “Dabo Tibi Coronam Vitae/C(a)esar as St. Maurice as St. Stephen,” explore the political and historical contexts of naming an enslaved person in the Hudson Valley. The piece was inspired by an archived newspaper notice that was placed by Samuel Bard (grandfather of the founder of Bard College) in 1815 searching for an enslaved man, named Cesar, who had escaped his household.

The piece poses the question: “Why name the lowest ranking member of the household with a historical name such as Caesar?...Perhaps (slave owners) were so arrogant that the irony didn’t even cross their minds or perhaps they reveled in it as a cruel joke,” Sovak says at the exhibit’s opening.

A view of Jean-Marc Superville Sovak’s “Dabo Tibi Coronam Vitae/C(a)esar as St. Maurice as St. Stephen.” Photo by Terry Roethlein

The panels depict Cesar as an amalgamation of three historical figures–St. Stephen, St. Maurice, and Julius Caesar. A 1795 illustration of St. Stephen, Bard College’s patron saint, bears the face of a 1520 depiction of St. Maurice, the first African saint, and the transformed St. Maurice/St. Stephen hybrid holds in his hand the head of Julius Caesar, as depicted in an 1801 illustration. Printed across all three panels are the Latin words Dabo Tibi Coronam Vitae, a quote from the Book of Revelations that means “I shall give thee the crown of life.” The fact that the phrase is also Bard College’s motto adds a dark irony to the mix.

“As a person of mixed race, I am always sensitive to the evidence of cultural hybridization that is the result of colonization and slavery — events which make up the DNA of this country, as well as my own,” says Sovak.

Sovak is also curious about what Cesar thought of his name. On the exhibit website, he writes, “It is said that in order to cross the Adriatic Sea undetected, Julius Caesar once disguised himself as a slave. Could the Black man named Cesar have taken his destiny as seriously as his namesake and disguised himself as a free man in order to cross over to self-emancipation undetected?”

Naming, Colonialism, and Patriarchy

“Swarajyalaxmi,” by Aarati Akkapeddi, explores colonialism and patriarchy through South Asian cultural traditions and how those systems can be embedded in a person’s name. The live performance piece concerns the artist’s centenarian grandmother, her life, and her name.

“I want the viewer who is unfamiliar with the historical context of my grandmother's namesake to understand that colonialism is in living memory. I want every viewer to think about how the political intersects with the personal,” says Akkapeddi.

Aarati Akkapeddi's live performance piece “Swarajyalaxmi” involved creating a kolam, a traditional South Indian decorative design, on the floor of the Opalka Gallery in Albany. Photo by Terry Roethlein

At the exhibit opening, Akkapeddi (they, them) drew on the gallery floor a kolam–a traditional South Indian decorative design that uses continuous intertwined lines of rice flour–to represent their grandmother’s name, Swarajyalaxmi. They also played an audiotaped interview with Swarajyalaxmi talking about her life–explaining how her name signifies independence in the colonial context and her resilience in the face of patriarchal oppressions, such as being married at age twelve.

“I want the audience–especially those who are familiar with the customs and context of my grandmother's experience–to think through the irony of her lack of independence and her experiences with patriarchal oppressions,” says Akkapeddi.

Naming, Listening, and Extinction

“Birding the Future,” a sound and photographic installation by Frank Ekeberg and Krista Caballero, is drawn from an ongoing series that explores the environmental and cultural implications of the decline of bird species for the past decade. The installation invites visitors to listen to endangered and extinct bird calls through recordings and to experience visionary avian landscapes through stereographs–superimposed images viewed through a stereoscopic lens. For this exhibition, the artists created a new series specifically focused on bird-naming practices and conventions, such as scientific naming that often disregards local and cultural knowledge about birds.

One of the stereographs from the "Birding the Future" installation by Krista Caballero and Frank Ekeberg. Photo by the artists.

The project website notes that “one in eight bird species is threatened with extinction.” The exhibit and the artists on view aim to make the viewer “wake up to the global extent of climate change” with birds as an “indicator species” of that problem.

In the installation, calls of endangered birds have been translated into Morse Code messages that are then amplified along with the calls of extinct birds. A real-time algorithm scales projected extinction rates to the duration of a day at the exhibition: the longer a viewer stays, the fewer birds they hear. The accompanying stereographs explore the history of human-bird encounters via imagery, poetry, and data. All of this creates a sensory experience that invites viewers to reexamine the way they look at and interact with the world and its species.

Partnership, Integration, and Engagement

Gwyneira Isaac, the lead for To Be—Named and director of Recovering Voices, an Indigenous language and knowledge revitalization program at the Smithsonian Institution, says collaborating with OSUN significantly amplified the reach of the project. Through OSUN, submissions for a forthcoming open access edited volume led to the inclusion of scholars and artists from 24 countries and 15 Indigenous and minoritized communities. “Having OSUN as a partner with the project enabled us to not only reach scholars from around the world but to also sustain a critical form of ongoing engagement with them,” she says.

Isaac says that the To Be—Named project strives to bring diverse scholars and disciplines into conversation with each other, as well as reach a broad and diverse audience. Current academic research must confront the colonial and racist histories that underpin it, then include and take seriously the different voices and experiences it integrates, she explains.

“This project offers stories about names and naming as a method for listening via inviting and engaging different forms of expertise,” she says. “During a critical turning point in how the balances of power and authority in the world are being redefined, the use of language has become a flashpoint over who has the right to define whom.”

The To Be—Named Exhibition at Opalka Gallery, Russell Sage College, Albany, New York runs until Saturday, October 14.

Full details here.

Post Date: 10-03-2023